The Elusive ‘Microgrid Tariff’ Begins to Emerge in California

The Elusive ‘Microgrid Tariff’ Begins to Emerge in California

The California Public Utilities Commission recently laid out the next step in how it plans to meet the demands of 2018 state law SB 1339 — creating a regulatory structure for commercially viable microgrid projects.

That’s a tall order, requiring policies that promote California’s carbon-free energy goals, give communities a route to secure backup power amid wildfire and heat-wave-driven blackouts, provide third-party commercial developers a way to earn revenue for the services they provide — all while preserving utilities’ role as the provider of power when the grid’s still up and running.

Amid the myriad complexities of this policy puzzle, one critical yet unresolved concept stands out: the need to create a microgrid “tariff” that specifies how a system’s multiple technologies, ownership structures, and costs and benefits can be applied to microgrid project after project. Piecing that puzzle together will be critical to scaling up the microgrid market quickly and efficiently.

Tariffs govern everything from interconnecting power plants and transmission lines to how utility customers pay their bills or get paid for the solar power they generate. But microgrids that combine multiple technologies, or utility-managed and privately owned infrastructure, have yet to be standardized in this way.

Last year, the CPUC declined to take up work on a tariff to focus its “Track 1” efforts on building microgrids in time for the 2020 wildfire season, a tight timeline that the state’s utilities weren’t able to meet with cost-effective projects. In fact, Pacific Gas & Electric ended up contracting for hundreds of megawatts’ worth of mobile diesel generators to fill this year’s gap in backup power as a stopgap measure.

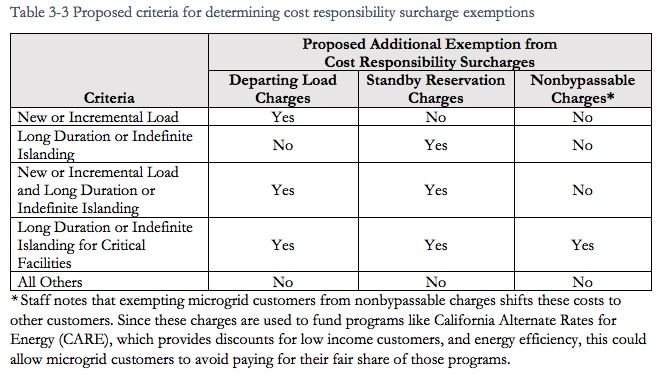

Last month’s launch of the proceeding’s “Track 2” includes a plan from CPUC staff (PDF) to define a simple microgrid tariff to bundle payments for multiple distributed energy resources into a single utility rate structure. The plan is focused on simple, single-customer microgrids, and it delineates how they could avoid paying both “departing load charges” for leaving utility service and “standby charges” for relying on the utility’s infrastructure for last-resort power. Exemption from those fees would depend on whether or not they’re new or existing loads, serve critical facilities or can self-power themselves indefinitely, as shown in the chart below.

But this doesn’t go far enough, according to groups trying to build their own microgrids. The Microgrid Resources Coalition, a trade group representing vendors including Engie, Eaton, Bloom Energy, NRG and Scale Microgrid Solutions, complained in its reply comments that the tariff proposal “appears to again be limited to a narrow class of microgrids,” in contradiction with SB 1339’s mandate.

Vote Solar and The Climate Center agreed with this contention in their joint comments, saying the proposed rate schedule “deals only with single-user or customer-sited microgrids, and offers nothing to support commercialization of community microgrids.” What’s more, the groups state, its focus on charge exemptions “offers no compensation for the value of services microgrids can provide to the grid.”

California’s community-choice aggregators (CCAs), which are major proponents of microgrid development, agreed in their joint filing that the CPUC’s proposal doesn’t go far enough. A “general microgrid tariff,” by contrast, “would cover all likely microgrid configurations,” including “utility-sited microgrids that serve multiple parcels/customers.”

And the joint CCAs have a model they’d like the CPUC to expand on: the Redwood Coast Airport Renewable Energy Microgrid being built in Humboldt County.

Looking at the Redwood Coast Airport example

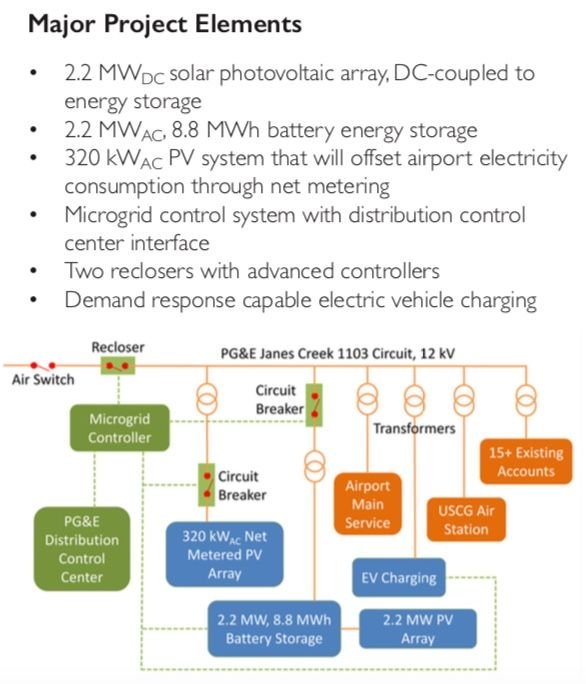

The $11.5 million project, funded by the county’s CCA Redwood Coast Energy Authority and the California Energy Commission, is “the first multi-customer microgrid in PG&E service territory, and one of the only ones in America as far as we know,” said Peter Lehman, the founding director of Humboldt State University’s Schatz Energy Research Center, the group leading the project.

It combines multiple customers, including the Redwood Coast Airport and the U.S. Coast Guard air rescue station, which are critical facilities for the county, along with 17 other customers. While Redwood Coast Energy Authority (RCEA) owns and operates the 2.2-megawatt solar array and 8.8 megawatt-hour Tesla battery system that powers the microgrid during emergencies, PG&E owns and operates the distribution systems across which that power flows.

Sharing existing infrastructure is much cheaper than forcing RCEA or its customers to buy and maintain a section of the distribution grid. But it also means “there’s got to be this bright, clear line between the distribution system operator and the generation system operator,” said David Carter, the Schatz Center principal engineer managing the project.

RCEA’s solar-battery control platform is isolated from PG&E’s grid control platform that runs the microgrid whether or not it’s disconnected from the grid at large. CPUC staff highlighted this as a critical cybersecurity measure to protect PG&E’s systemwide grid operations from intrusion.

The “bright, clear line” also applies to the tariff design, in terms of who’s getting paid for supplying the energy and the infrastructure it runs over during both islanded and “blue-sky” conditions, Carter said. A significant investment is needed in equipment to isolate the system and run it independently, and how best to split those costs is still being worked out, he said.

These infrastructure costs will be governed by a Microgrid Infrastructure Cost Recovery Tariff. Since RCEA requested the microgrid and its customers reap the benefits, RCEA will pay for certain upgrades. But because it’s a pilot project, PG&E is also contributing, Carter said. Future utility-operated microgrids will need to consider how to handle that cost-sharing issue.

RCEA’s solar and battery system generates about seven times the electricity needed by the airport, Coast Guard station and other customers, Lehman said. That will allow the microgrid to run for weeks without its existing diesel backup generators coming on — hence the “renewable energy” in its name — and it’s also in line with RCEA’s goal as a CCA to build out local clean energy projects.

But to make the economics work, RCEA must sell the power on the wholesale market, through a hybrid solar-storage tariff (PDF) now being finalized by state grid operator CAISO, Carter said. “In blue-sky conditions, this is a CAISO-controlled asset,” he said.

The project is exploring the complexities of supplying energy and grid services to multiple classes of customers in both islanded and blue-sky states. All of the power users on the site are RCEA customers, but RCEA itself is a customer of PG&E, and the electric-vehicle chargers it’s installing on the site will be under the utility’s tariffs.

That will provide the opportunity to investigate two different types of tariffs to both classes of customer: an Islanded Grid Services Tariff with revenue flowing to both PG&E as the grid infrastructure operator and RCEA for energizing the microgrid, and an Islanded Energy Tariff payable to RCEA as the provider of electrons.

All told, “the goal is to get the framework and standardized design that PG&E could accept rather quickly” for other projects, Carter said. While the Redwood Coast project is funded by CEC’s EPIC grant program, PG&E is using it as a model for a separate effort to support microgrid development for the fire-threatened Northern California communities it serves.

PG&E takes a “good first step”

PG&E’s “Community Microgrid Enablement Tariff” (PDF) sets rules for how local communities, tribal governments or CCAs can build up to 20 megawatt systems in high-fire-threat areas that support critical facilities and at least one other customer. It’s backed by $27 million through 2022 for PG&E to install the necessary utility-side equipment and controls.

The tariff will govern eligibility, engineering studies, development of the microgrid assets and the transitional operation of the microgrid, as well as how services are provided during islanded and grid-connected conditions, PG&E spokesperson Paul Doherty said.

Unlike PG&E’s rejected plan to install natural-gas generators at its substations, the community microgrid plan envisions third-party ownership, with a focus on clean resources. The Redwood Coast Airport project is serving as a model, Doherty said, including how communities’ development partners can support the technical challenges of running their power over PG&E’s lines.

At the same time, the systems involved will be eligible to provide distribution services and participate in demand-side management programs and CAISO markets while they’re connected to the grid. That’s critical to allow the solar, batteries, load controls and other microgrid assets to earn revenues during blue-sky conditions to pay back the costs of engineering them to keep the power on when they need to island from the grid.

For groups asking the CPUC to create a statewide microgrid tariff, PG&E’s proposal is a good first step, Ed Smeloff, Vote Solar’s director of grid integration, said. But he also noted that “PG&E explicitly retains the rights to pull it” if the partners can’t meet the technical terms of the tariff. “It’s clearly intended to be testing the waters.”

Still, it lays the groundwork for a logical step for microgrids, he said, putting their combined energy, capacity and grid stabilization services to use not just for their customers, but for the grid at large.

Distribution Support Services Tariffs: The future of microgrids?

The CPUC staff paper describes this concept as a Distribution Services Support Agreement (DSSA), a tariff that sets localized distribution services and provides a market pathway to serve them. Those could include replacing grid investments under the CPUC’s Distribution Investment Deferral Framework, or other services where “no specific organized markets yet exist,” as with dynamic voltage support to increase a utility’s distributed energy hosting capacity.

The IDEA Education Foundation, in partnership with the Energy Foundation, recently produced a general educational white paper on the concept. The Microgrid Resources Coalition supports this framework as a logical way to value the ability of microgrids, MRC counsel and board member Christopher Berendt said.

“With DSSAs, you’re adding greater controls for utilities to be able to conduct the dispatchable [distributed energy resource] concert, to be able to dispatch at a segmented level,” said Berendt. “You want the microgrid to have services that the utility can call on to help it reduce the cost of service to the rate base, and provide better smart grid services that help communities become more resilient and decarbonize.”

“There are many ways for utilities to support or partner with microgrids, and DSSAs are a prime example,” MRC counsel and board member Baird Brown added. While the MRC sees microgrid commercialization driven by customers, “it’s reasonable for regulators to reward utilities that can tap microgrids for grid services they would otherwise have to spend more on to procure themselves.”

The Schatz Center is also exploring the potential for the Redwood Coast airport microgrid to help out in these ways, Carter said. The airport is at the end of a distinct PG&E circuit that could face overloads from any more solar added to the microgrid’s large-scale system, he noted. But if the microgrid could island and curtail to protect the circuit from the rare instances of overgeneration, it could allow PG&E “to increase hosting capacity without having to do expensive upgrades.”

“We know the grid constraints upstream, so we can monitor the power in real time and proactively through prediction and forecast,” he said. “If PG&E is rolling out an [advanced distribution management] system over the next five years, they’ll be able to predict that overgeneration condition and seamlessly disconnect the microgrid.”

The CPUC doesn’t include these more advanced microgrid tariff concepts in its Track 2 microgrids proposal. Instead, they are relegated to a separate staff concept paper laying out its plans for Track 3. But as we saw from the comments of parties including the MRC, Vote Solar and the joint CCAs, there’s obvious interest in moving ahead with them as quickly as possible.